Beyond Blessing and Blight

Dark magick as craft, boundary, and balance in the Germanic imagination

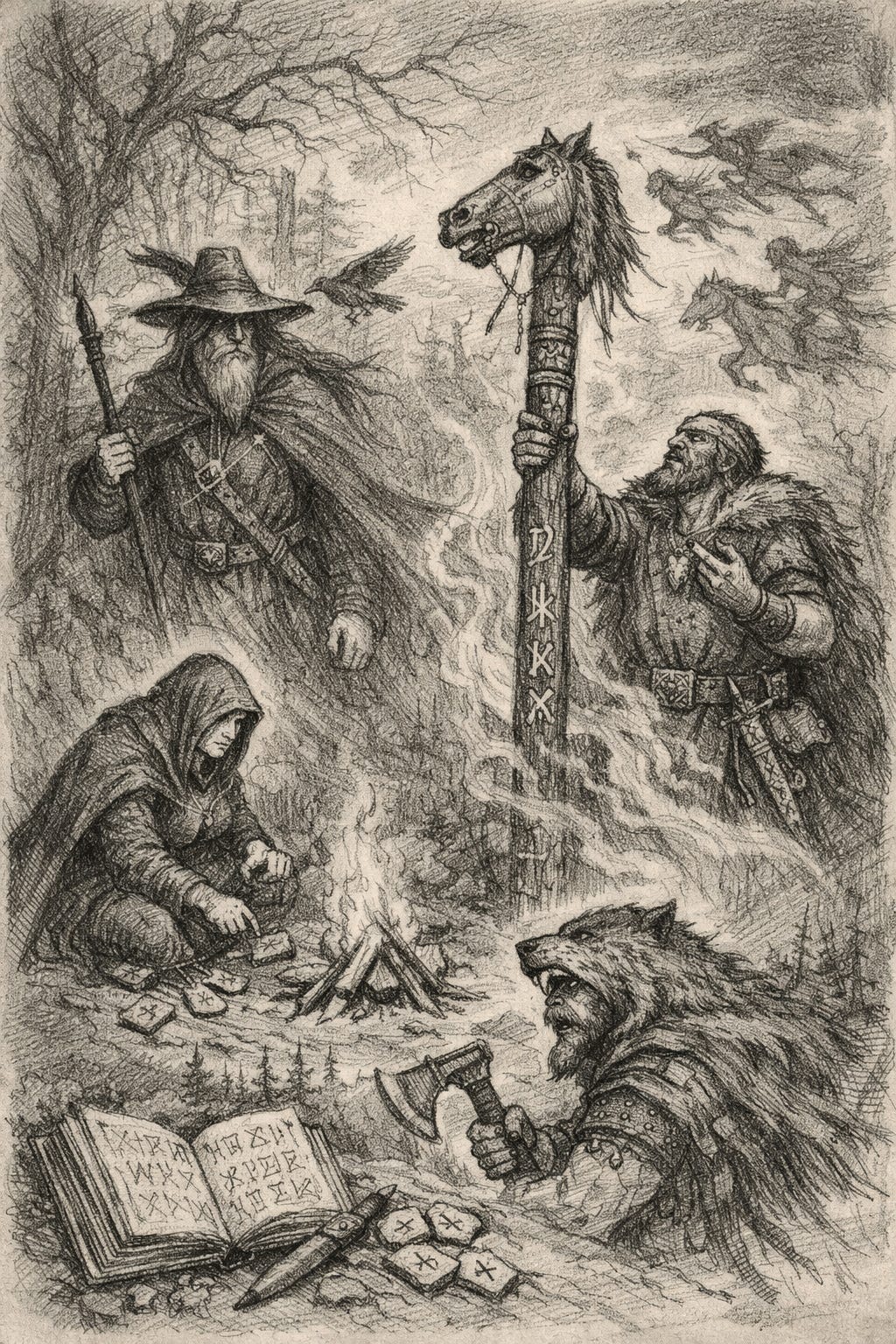

Twilight settles over a primeval wood. In that liminal light, the old gods walk unseen, weaving spells into wind and branch. Ancient voices speak of Odin, the Allfather, who sacrificed himself on the tree to snatch up secret runes of power. He is a figure striding beyond simple moral borders, a god who blesses and curses with equal fervor. In the Hávamál, a poem of the Poetic Edda, Odin boasts of spells that can both help and harm. “A sixth I know,” he says, “if some thane would harm me… on his head alone shall light the ills of the curse that he called upon mine”. He knows a tenth charm as well, to send witches riding at night off course, bewildering their senses until they wander home foolish and spent. These age-old verses do not tremble before the specter of “dark” magick. They present it as knowledge, songs of power to ward off harm or to repel malice with malice. Within the cosmology of the Germanic peoples, the line between a healing chant and a hex was often one of intent and perspective. To stand under that rune-lit sky is to see magick as a tool, a birthright of gods and heroes, intrinsically neither virtuous nor wicked.

Consider the Norse creation myths and hero tales. They rarely draw a stark line dividing white from black magic. The same seiðr (sorcery) that can curse a foe can also heal or foresee fate. Freya, goddess of love and war, was said to teach the art of seiðr to Odin. In saga and song, knowledge is power, whether it comes clothed in light or in shadow. The Volva, the prophetic witch-woman of the North, travels between worlds in trance to seek answers. Such a figure appears in Völuspá, prophesying doom to the gods, and yet her dark vision is part of the cosmic balance. In the mythic worldview, even destruction has its place. As one modern scholar of Icelandic magick notes, it is an error to think the pre-Christian north had no such thing as “evil magic” at all. The Edda itself shows spells wielded against practitioners of malice. What was evil to that pagan mind was not the method or the uncanny source of power, it was the aim of the working and its effect on the community’s well-being. A curse to halt a murderer or oath-breaker might be grim, but it was a justice, not a sin. In the firelight of the mead hall, where warriors listened to skaldic poetry, there was respect for the deep gray hues of reality. Dark magick, in its many runic and herbal guises, was one thread in the tapestry of wyrd, the unfolding fate, and it served those bold enough to weave it.

In the old sagas of Iceland, one can hear the earthier, iron-toned truth of dark magick in practice. Take the tale of Egill Skallagrímsson, a warrior-poet who lived by his wits and his sword around the tenth century. Egill was a man who knew both the gentle art of verse and the brutal art of vengeance. When King Eiríkr Bloodaxe and Queen Gunnhildr wronged him, Egill did not meekly accept exile or defeat. Instead, he performed one of the most infamous acts of curse-work in the literature of the north. He raised a níðstǫng, a nithing pole, on a forlorn headland facing the mainland. He slaughtered a horse and mounted its severed head atop a pole, carving runes of malediction into the wood. Standing by the grisly standard in the salt wind, Egill spoke a formal curse, calling upon the landvættir, the land-spirits, to drive the king and queen from the country. “Here set I up a curse-pole, and this curse I turn on King Eiríkr and Queen Gunnhildr,” he declared, turning the horse’s grimacing head toward their lands. “This curse I turn also on the guardian-spirits who dwell in this land, that they may all wander astray, nor find their home again till they have driven out the king and queen.” Having spoken, he slammed the pole into a rocky cleft and left it standing against the sky.

To later Christian ears, such a rite sounded like the very image of heathen evil, a blasphemous conjuration. Yet in Egill’s culture, this was an act of personal sovereignty and balancing of accounts. By Norse custom, a man unjustly outlawed or persecuted by his rulers had few official recourses, so he invoked older, occult justice. The saga makes no moralizing comment that Egill is damned for this deed. Rather, it is presented as the natural response of a proud man defending his honor by calling on deeper powers. The curse of the nithing pole was feared, yes, and dark in its imagery, but it was deeply personal and essentially judicial. It aimed to restore balance where human law had failed. In Egill’s saga and others, great men and women do not hesitate to use runes and rites to heal or to harm as circumstance demands. The lore records another saga character crafting a wooden níð with a carved human head and the skin of a dismembered horse, raising it against a coward who shirked a duel. The intent was to shame and expel a toxic presence, not to wreak random havoc. In these stories, such magick is an extension of the person’s will and duty. It underscores that within the pagan moral cosmos, to curse an oath-breaker or tyrant could be a righteous act, heavy with venom but aimed at a greater equilibrium.

Even the land itself partakes in this tapestry of curse and redress. The vengeful pole of Egill did more than threaten human targets; it enlisted the very spirits of nature in its cause. This reflects how intimately the Germanic peoples saw themselves bound to the land and its unseen guardians. To weaponize a landvættir against an enemy was perilous, yet it acknowledged a truth. The spirits could choose sides based on right or wrong, plenty or famine, honor or dishonor. This required the sorcerer to stake his life-force and reputation on the justice of his cause. If the curse proved unjust, it might well backfire, as hinted in rune lore and folktale. Indeed, one of Odin’s spells in the Hávamál is explicitly to rebound an evil curse back upon a treacherous caster. The sagas quietly teach that wielding the níðstǫng or carving death-runes on a whalebone carries ethical weight. The act itself is neutral power. The heart behind it tips the scale toward havoc or healing. Egill’s cold fury, cast into runic form, was a way of speaking a truth when no other speech would be heard.

In the world of the Viking Age, magick bled into daily life as quietly as the color of dawn into morning. Wise women wandered from farm to farm, dispensing prophecies and counsel in times of hardship. Warriors inscribed spells on their blades and took up animal skins and berserker rages in Odin’s name, blurring the line between man and beast. The Romans and other outsiders who encountered the Germanic tribes took note of these uncanny proclivities. The historian Tacitus, writing in the first century, remarked with respect that the Germans believed women carried a sacred gift of prophecy. They would not make an important move without consulting a seeress. One such prophetess, Veleda, held such sway during the wars of Rome that she was treated as a deity by her people. To Roman sensibilities this might have seemed like superstition, but Tacitus recounts it without ridicule. He saw a culture in which the mystical feminine was revered, not burned. The advice of a wise woman, perhaps gained through night-long trance or the casting of carved lots, was simply another form of counsel. In that society, magick and spirituality were woven into governance and war-councils. A chieftain might delay battle because the songs of the spae-wife warned of ill omens. Far from being viewed as “black magic,” these divinations served the tribe’s survival and were honored for their accuracy and power.

Likewise, the warriors themselves engaged in what later ages might label dark sorcery without a second thought. The berserkers, for instance, were said to take on the spirit of the bear or wolf in battle, a condition possibly induced by ritual, intoxication, or sheer frenzy. This was a holy rage given by Odin, rendering them impervious to iron for a spell of time. In the Viking Age worldview, to fight with such ferocity was a gift from the gods, though it unleashed a dangerous, animalistic force. The distinction between a blessed fury and a demonic possession was not sharp. What mattered was whether it served the folk and earned glory. We hear also of warriors and wizards using galdr, sung spells, to churn up storms at sea or bring nightfall early. These acts could scatter an enemy fleet or allow an escape. They were tactics as neutral, in themselves, as forging a sharper sword. They were judged by their effect and the fairness of their aim.

Germanic culture’s ethical lexicon did not contain the rigid good versus evil dichotomy that later Christian missionaries brought. There was a word for evil, in Old Norse illr, or níð for social wrong, but it attached to deeds and consequences rather than to the abstract origin of a power. A sorcerer, a galdra-maðr, was just a person who did magic. Whether for benevolence or bane depended on the individual case. The lore of the Norse is rich in tales of magick being a craft, even a profession, approached pragmatically. In Eirik the Red’s Saga, when Greenland fell into famine, the settlers invited a volva named Þorbjörg to perform seiðr and foretell when scarcity would end. She arrived in a blue cloak trimmed with gems and a headpiece of black lamb, carrying the staff of her office. The community gathered in respectful silence as she sang the spirits awake. Here was dark magic, necromantic song and contact with unseen powers, put to use for hope and sustenance. The only Christian present, a young woman, at first feared to participate, yet even she ended up assisting the rite by singing the old chants. The saga does not depict the volva as wicked. She is dignified, even revered for her connection to the hidden realm. The dark magick here is the deep root reaching into the soil of fate, and the community waters it with faith because it promises guidance.

Throughout these accounts, one senses that the pre-Christian Germanic peoples had an animist, holistic view of the world, where every tree might house a spirit and every spoken curse might take wing. Magic was a neutral currency in that world, minted from willpower and sacred knowledge. Just as iron could be forged into a plowshare or a sword, the runes and incantations could heal a sick child or smite a rival. This dynamic view persisted in folk culture long after the official conversion of these lands to Christianity. Medieval law codes from Iceland and Norway did outlaw harmful witchcraft, but they often did so in the same breath as outlawing poison or physical crimes. A murder by blade and a murder by curse were both punishable, because both caused harm unjustly.

When Christianity spread across the northern lands, the narrative of magick began to change. The new religion brought with it a strict binary. Deeds and even thoughts were either in service of God or in league with the Devil. In this imported cosmology, there was little room for the old neutral ground. The very same spells that a village wise man might have used to bless the fields or banish a fever were recast as diabolical, unless they were couched in Christian prayer. By the late medieval era, Icelanders and Norse folk still practiced magick, but now under the anxious gaze of Church and law. Yet the practice did not die. In fact, it sometimes hid in plain sight among the educated elites. History records that in Iceland it was often clergymen themselves who became the most adept sorcerers. The bishops and learned men compiled grimoires, mixing Latin exorcisms with runic symbols, scripture with sigil. One notorious example is Gottskálk the Cruel, a sixteenth-century bishop of Hólar, whispered to have compiled the Rauðskinna, the Red Skin book of magic drawing on pagan spells. Such figures operated in a gray zone. officially condemning witchcraft even as they themselves sought power in old magickal texts. Such hypocrisy proves the neutrality of magic itself; it will serve whoever learns its grammar, be they saint or sinner.

Dr. Stephen Flowers, a contemporary scholar of the Northern grimoires, observes that Iceland’s post-conversion magicians largely kept the pagan ethos in their practice. What mattered to them was whether a spell helped the good of people, livestock, and land, or whether it caused unjust harm. Their moral compass remained aligned with their ancestors’. Good magic protected the thriving of the community. Harmful magic sought its ruin. The symbols they employed could be the cross or the Thor’s hammer, angelic names or the names of Odin and Freya, without much worry. What counted was the result. A fragment of a seventeenth-century Icelandic grimoire might invoke Jesus in one line and Odin in the next when chasing away a nightmare. In the mind of the magician, this was pragmatic rather than incoherent. The old gods and the new could be tools toward a rightful end. To survive in a harsh life, one would gladly pray to the White Christ on Sunday and whisper an old Galdr on Monday if it kept the farm prospering.

As Christian law hardened, tolerance for unsanctioned magick waned. By the seventeenth century, even carving harmless runes could arouse suspicion of witchcraft. The trials and burnings that ravaged Germany and Scotland touched Iceland and Scandinavia more lightly, but still they left scars. Society was being forcibly reoriented to view all magick as inherent evil, a pact with the Devil rather than a pact between a person and the living cosmos. This doctrinal shift cast a long shadow. Much of the subtle wisdom of magick went into hiding, into folktale and whispered family traditions. Yet it never disappeared. In secret, the craft endured, passed down in scraps of parchment and lullabies that doubled as spell-songs. Even in witch-hunting manuals, one sees echoes of the older morality. A witch was often accused of blighting crops or causing illness, concrete harms. The crime was not consorting with earth spirits per se. It was using any means to maliciously wreck livelihoods. In this way, the kernel of the ancient worldview persisted. Magick itself was not the sin. Cruelty was.

Centuries later, modern practitioners in Northern traditions seek to peel away those later overlays of fear and stigma. They study the Encyclopedia of Germanic Mythology by Claude Lecouteux, or pore over translations of the Galdrabók, the Icelandic Book of Magic, to rediscover how their ancestors saw the unseen. What emerges is a picture of dark magick as an aspect of nature’s own cycles. Just as winter’s cold and summer’s heat are both necessary, the baneful runes and the healing runes complete each other. A curse can be seen as the winter of a soul, a time to wither what is diseased or unjust, so that spring can come anew. The old Icelandic word fjörlausn, meaning life-release, referred to a ritual of lifting a curse or disease, but it frames it as releasing the vital spirit from bondage. Sometimes that release was gentle. Other times it required stern measures, even a symbolic confrontation with death. In all cases, the focus was on restoring balance.

In reclaiming the neutrality of magick, we step into a birthright of responsibility and self-knowing. The shadows once shunned as evil become familiar, even honest in their presence. One practical way to taste this truth is through a simple mindfulness practice of sovereignty and boundary. At day’s end, find a quiet space as dusk draws in. Stand with your feet firmly on the earth and let your eyes rest on the meeting of light and shadow in the dimming air. As you breathe, imagine a circle traced around you on the ground, a subtle boundary like the edge of twilight. Feel the weight of your body and the solidity of your presence within this circle. Now acknowledge the darkness around you as a living substance. The night air carries the scent of soil and distant pine. The gentle press of shadows reveals the contours of unseen things. Rather than pushing away the darkness, invite it to be a witness to your space. With a slow exhale, plant your inner staff into the center of your circle. You may visualize a strong hazel pole, like Egill’s, unadorned by any curse. This is your claim. You have a right to be here, to feel safe and whole. In your mind or whispered softly, state a simple truth. I stand in my own spirit. What comes to me, comes through my consent. There is no elaborate ritual needed. No herbs or incantation. Only the quiet power of intent drawing a line. You may sense in that moment a kinship with the Volva of old or the lone magician on a starlit fjord. The awareness arrives that the darkness is not an enemy. It is a mirror and a buffer, an old companion wrapping your small circle in vast silence.

This mindful act is an ethical expression of dark magick because it recognizes boundary and sovereignty without aggression. It does not banish the dark. It engages it. In standing calmly at the threshold of night, you practice the art of the wise, neither cringing before the shadow nor allowing it to overrun you. The fear that dark magick must be malevolent dissolves here. What remains is clarity, a delineation of self that harms none. As you conclude the practice, notice the steadiness in your bones and breath. The world around may be dark, but it is rich with life and meaning. You have met the shadows within and without and found them morally neutral, shapes awaiting the form given by your conscious will. In that realization lies a quiet empowerment that the pagan forebears understood. Beyond good and evil, in the deep night of the soul, magick simply is, and it is we who lend it heart.

[My public work remains a free offering. Supporters receive the more intimate writings that arise from practice itself. If you can spare $5 each month, I will place those gifts in your hands. If you cannot, send me a message and I will give you the tier.]

There's something in the idea of magic as neutral currency that resonates with how I think about ritual in Mediterranean contexts; the same gesture can bless or bind depending on who's holding the knife. The landvættir as witnesses who can choose sides based on justice adds a layer I hadn't considered. Curious if you've looked at similar patterns in Southern European folk practice.

I always thought it was a shame that Christianity was so hugely successful at converting Europe and stamping out paganism, because paganism was way more badass and heavy metal.

Nice to see there's a revitalized interest in, ironically, the deeper and more original Western civilization before it was converted at the sword.